Food and Nutrition Security: An Essential Element of Caribbean Resilience

Key Messages

- Already one of the sickest regions per capita in the world, the pandemic is exacerbating food and nutrition insecurity in the Caribbean.

- Food and nutrition security helps build resilience by promoting a healthy population, thereby minimising the strain on families, health care systems and public finances. It is a smart investment, which enhances human capital. The pandemic has underscored the imperative of a steady, resilient and more indigenous food supply in the Caribbean.

- An all of society approach is essential to address the food and nutrition challenges of the Caribbean and must, of necessity, include health-friendly macroeconomic policies; social marketing; improved logistics; and the deployment of digital technologies.

Introduction

One of the important lessons of the pandemic is the criticality of food and nutrition security.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines food security as being realised when “all people at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preference for an active and healthy life.”

This definition suggests that food security is a multifaceted concept, which considers not just the supply of food, but its accessibility, price, safety and nutritional value. When asked which groups were most at risk of food insecurity from the pandemic, the FAO noted, inter alia, vulnerable communities affected by other crises, as well as Small Island Developing States which depend heavily on imports, remittances and which are vulnerable to climatic events.

At the outset of the pandemic, you may well recall the frenzy at our supermarkets as we rushed to stock up, fearful of shortages. Indeed, as we learned of major disruptions to global supply chains stemming from lockdowns in supplier countries, we wondered what if the ships from Miami to the Caribbean do not come as scheduled. How would we survive? This anxiety-laden question was less about industrial supplies and more about our food.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines food security

Supply chain disruptions have led to shipping container shortages and soaring freight rates, which have resulted in rising shipping costs. Therefore, since June 2020, global food prices have risen to reach one of its highest levels in more than six years, as seen from the FAO’s Food Price Index[1] (Figure 1). These developments highlight the vulnerability of our region’s food systems to potential shocks.

The ECCB has estimated a contraction in Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) GDP of 14.0 per cent in 2020, mainly attributable to the adverse effect of the pandemic on service-related sectors, especially Tourism.

This COVID-19 shock has led to unprecedented job losses and is constraining low-income households’ ability to spend on food, particularly locally grown healthy foods. Governments have offered care and relief packages to the most vulnerable and impacted but many of these programmes have now ended because of severe fiscal constraints. The Love Box programme in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines was an innovative way to deliver healthy and nutritious food to needy households while supporting farmers and avoiding massive spoilage. However, such a programme is a function of fiscal capacity. Alas, the eruption of the La Soufrière volcano has wiped out the major food belt of Saint Vincent, resulting in a supply problem.

Similar to governments, most social security systems in the ECCU offered 3-6 months of unemployment support in the early months of the pandemic. However, the reality is that these payments are unfunded, as most of the systems in the ECCU do not explicitly provide for unemployment benefits. This is a deficiency that our policymakers must urgently address, given the frequency of shocks on employment and the imperative of protecting the long-term sustainability of social security systems - our region’s most important social safety net.

The Heath Impacts of the Pandemic

There is a clear and present danger that the pandemic is exacerbating pre-existing health issues with a disproportionate and devastating effect on the poor and most vulnerable households. Indeed, a recent study by some United Nations agencies operating in the Caribbean points to a reversal in the gains made in respect of reducing undernourishment in the Caribbean (Figure 2).

The income losses from the pandemic are limiting households’ ability to purchase nutritious food. Already a common practice before the pandemic, it is highly likely that these households are purchasing and consuming cheaper, less healthy alternatives to the detriment of their health.

The pandemic has overshadowed many health issues but it has also shed light on others. Indeed, our region’s high incidence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has increased the susceptibility of our population to COVID-19.

The Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, Sir Hilary Beckles recently made the startling observation that the Caribbean, per capita, is the sickest region in the world. This dubious distinction should focus our minds on the immediacy of the task at hand – rapid enhancement of food and nutrition security.

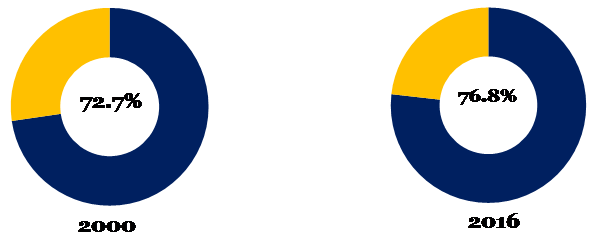

A 2020 report from the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA) indicates that deaths from non-communicable diseases (including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and hypertension) made up 76.8 per cent of all deaths in 2016, up from 72.7 per cent in 2000. The report cites an unhealthy diet as one of the main NCD risk factors.

report from the Caribbean Public Health Agency

More than two decades ago, as a young economist in Grenada’s Ministry of Finance, I recall doing a paper on the Macro-Economic Policies Related to Food and Nutrition in Grenada. The key finding of that paper was this: Grenadians were eating more but were not eating better. I suspect this same finding holds true in many Caribbean countries where, even as per capita income has risen, so have our consumption of ultra-processed foods.

Our Food Import Bill

Our region’s reliance on food imports is significant. In 2019, ECCU food imports were valued at EC$1.6 billion. In 2020, that bill was EC$1.4 billion (Figure 4).

The agricultural and fishing sectors, on average, accounted for only about 2.0 per cent of GDP (Figure 5).[2] Our increasing reliance on imports highlights our region’s food system’s potential vulnerability in the event of major supply disruptions.

Response of ECCU Member Countries

Since the pandemic, ECCB member governments have stepped up efforts to ensure a sufficiency of local food as a pre-emptive strategy to safeguard and promote food and nutrition security. Although these efforts are heartening, they need to be sustained. Some of us may recall the food crisis in 2008, when food prices rose dramatically on account of some weather events. At that time, the Jagdeo Initiative was advanced and it seemed as if our region was poised for a major breakthrough on food and nutrition security. Alas, as the weather improved and food prices fell, interest waned and a subsequent change in the political climate meant no further progress on this regional initiative. On this occasion, our region must avoid this error.

As part of its response to the pandemic, the ECCB Monetary Council approved a Programme of Action for Recovery, Resilience and Transformation in October 2020. Under the pillar of Resilient and Inclusive Growth, the Monetary Council is targeting a 25 per cent reduction in the 2019 ECCU Food Import Bill over the next three years – a savings of $400 million.

What will it take to achieve this target?

I advance some suggestions in my Call to Action.

Call to Action

In enhancing food and nutrition security and reducing our regional food import bill, I posit the following suggestions:

- A massive and sustained public awareness and education campaign about our food choices and their life and death consequences. The bottom line here is that we must choose life.

- A demonstrated commitment to place women at the centre of the public discourse on our food and nutrition security agenda. After all, as Keithlin Caroo of Saint Lucia so eloquently asserted during our 5th Growth and Resilience Dialogue earlier this year, “teach a woman to farm and feed a country for eternity”. In this regard, we should look to scale up, across the ECCU, the work she is doing with the Agriculture Academy.

- An insistence on good nutrition in our school feeding programmes. The bottom line here is to nurture taste and preferences and thereby raise healthier children. Never forget, “sugar” is an acquired taste.

- The deployment of digital technologies to improve the quality, reliability and resilience of healthy and locally grown food. For example, there are already encouraging efforts with aquaponics but these pilot farms must be taken to scale. In addition, technology professionals can partner with local producers to set up e-commerce platforms (similar to Agri-linkages), to offer all-in-one digital markets where consumers and businesses can interact. The ECCB’s digital currency (DCash) could facilitate payment for such services.

- The urgent enhancement of regional transportation systems would improve cross-border logistics and distribution across our archipelagic chain. Improved regional shipping systems and logistics would make more fresh produce available for citizens, residents and visitors and would reduce the large volumes of imported produce, thereby saving precious foreign exchange.

- The adoption of macro-economic policies that appropriately tax ultra-processed foods and better incentivize local production. Admittedly, this is not an easy policy issue, as the ultra-processed foods, at first instance, are currently far cheaper. Except, they are not. Ultimately, we pay enormous health bills and experience a diminished quality of life because of NCDs. Moreover, far too often, we pay with our lives.

- Clear and measurable food production and import reduction targets for each member country in the ECCU to secure the 25 per cent reduction sought by the Monetary Council.

- The adoption of an all of society approach to the enhancement of food and nutrition security with clear roles of responsibility for government, private sector and individuals. The role of personal responsibility in this endeavor cannot be overstated.

Conclusion

The pandemic highlights the dependence and increasing vulnerability of our region’s food system on external markets.

Food security should not be treated as a topical issue, which takes the spotlight whenever there is a crisis and fades into the background when the crisis subsides. Instead, our region ought to place greater emphasis on the agri-food sector by supporting small farmers; increasing investment in climate-smart technologies; and developing digital marketing and distributional platforms to enhance the sector’s resilience. Indeed, we should see the pandemic as an opportunity to implement meaningful and long-term solutions for regional socio-economic transformation.

Will we?

- The FAO’s Food Price Index tracks monthly changes in the international prices of traded food commodities.

- The minimal contribution of the agricultural sector has been compounded by the effects of climate change and natural disasters on the sector.

Acknowledgement

The ECCB acknowledges the contribution of Ms Martina Regis, Senior Economist (Ag.), Research Department, in the preparation of content for this blog.

About the Author

Timothy N.J. Antoine has been the Governor of the ECCB since February 2016. He is passionate about the socio-economic transformation of the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) and regards it as the pathway to shared prosperity for the people of the ECCU.

About the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank

The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) was established in October 1983. The ECCB is the Monetary Authority for: Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Christopher (St Kitts) and Nevis, Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.